|

Article Information

|

Authors:

Heleen French1

Emmerentia du Plessis1

Belinda Scrooby1

Affiliations:

1School of Nursing Science, North-West University, Potchefstroom campus, South Africa

Correspondence to:

Emmerentia du Plessis

Email:

emmerentia.duplessis@nwu.ac.za

Postal address:

Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom 2520,

South Africa

Dates:

Received: 24 Mar. 2010

Accepted: 18 Nov. 2010

Published: 16 May 2011

How to cite this article:

French, H., Du Plessis, E. & Scrooby, B., 2011, ‘The emotional well-being of the nurse within the multi-skill setting’,

Health SA Gesondheid 16(1), Art. #553, 9 pages.

doi:10.4102/hsag.16i1.553

Copyright Notice:

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: OpenJournals Publishing. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

ISSN: 1025-9848 (print)

ISSN: 2071-9736 (online)

|

|

|

|

The emotional well-being of the nurse within the multi-skill setting

|

|

In This Original Research...

|

Open Access

|

• Abstract

• Opsomming

• Introduction

• Background

• Problem statement

• Objectives

• Definitions of key concepts

• Level-2 hospital

• Professional nurse

• Enrolled nurse

• Nurse assistant

• Multi-skill

• Emotional well-being

• Research method and design

• Research approach

• Research method

• Population

• Sample

• Data collection

• Data analysis

• Literature control

• Ethical considerations

• Trustworthiness

• Results and discussion

• Positive experience of the multi-skill setting

• An opportunity to gain experience

• An opportunity to prepare for possible further studies

• An opportunity for task sharing

• Negative experience of the multi-skill setting

• Misrepresentation of the term ëmulti-skills settingí

• Stress brought on by staff shortages

• Subjective consequences of task overload

• Unreasonable staff allocation

• Duties beyond scope of practice

• Insufficient resting time

• Negative perception towards management

• Personal coping mechanisms within the multi-skill setting

• Task prioritisation

• Faith

• Self-motivation

• Mutual support amongst colleagues

• The promotion of the emotional well-being of nurses within the multi-skill setting

• Personal promotion of emotional well-being

• Managerial involvement to promote emotional well-being

• Limitations of the study

• Recommendations

• Recommendations for further research

• Recommendations for nurse education

• Recommendations for nursing practice

• Conclusion

• References

|

|

The emotional well-being of nurses working in a multi-skill setting may be negatively influenced by their challenging work environment.

A qualitative, explorative, descriptive and contextual study was conducted to investigate this phenomenon. The purpose of this study

was to explore and describe the experience, as well as perceptions of coping mechanisms, of nurses working in the multi-skill setting,

and to formulate recommendations to promote their emotional well-being. The population consisted of nurses working in a multi-skill

setting (a Level-2 hospital) and included professional nurses, enrolled nurses and nurse assistants. An all-inclusive sample was used.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with three professional nurses, six enrolled nurses and one nurse assistant. These interviews

were analysed according to the method described by Creswell (2003:192). The findings indicated that nurses have positive as well as

negative experiences of the multi-skill setup. They cope by means of prioritising tasks, faith, self-motivation and mutual support.

They also made suggestions for the promotion of their emotional well-being, on personal as well as managerial levels. Recommendations

for further research, nurse education and practice were formulated. Recommendations for practice include ‘on-the-spot’

in-service training, appropriate task allocation, clearly defined scope of practice, time for rest and debriefing, strengthened

relationships with management, promotion of strengths and creating a support system.

Die emosionele welstand van verpleegkundiges werksaam in ‘n multivaardigheidsopset kan moontlik negatief beÔnvloed word deur die

uitdagende werksomgewing. ‘n Kwalitatiewe, verkennende, beskrywende en kontekstuele studie is uitgevoer om hierdie verskynsel te

ondersoek. Die doel van hierdie studie was om die ervaring van verpleegkundiges, asook hul persepsies van hanteringsmeganismes, in ‘n

multi-vaardigheidsopset te verken en beskryf, sowel as om aanbevelings vir die bevordering van hulle emosionele welstand te formuleer. Die

populasie het bestaan uit verpleegkundiges werksaam in ‘n multivaardigheidsopset (‘n Vlak-2 hospitaal) en het professionele

verpleegkundiges, ingeskrewe verpleegkundiges en verpleegassistente ingesluit. ‘n Alles-insluitende steekproef is gebruik.

Semi-gestruktureerde onderhoude is met drie professionele verpleegkundiges, ses ingeskrewe verpleegkundiges en een verpleegassistent

gevoer. Hierdie onderhoude is volgens die metode deur Creswell (2003:192) beskryf, geanaliseer. Die bevindinge het getoon dat verpleegkundiges

positiewe sowel as negatiewe ervaringe van die multivaardigheidsopset het. Hulle gebruik taakprioritisering, geloof, selfmotivering en

wedersydse ondersteuning as hanteringsmeganismes. Hulle het ook voorstelle gemaak vir die bevordering van hul emosionele welstand, op

persoonlike sowel as bestuursvlak. Aanbevelings vir verdere navorsing, verpleegonderwys en die praktyk is geformuleer. Aanbevelings vir

die praktyk sluit in ‘in-die-oomblik’ indiensopleiding, toepaslike taaktoewysing, duidelikheid oor bestek van praktyk, tyd

vir rus en ontlading, verbeterde verhoudings met bestuur, bevordering van sterk karaktereienskappe en die skep van ‘n ondersteuningsnetwerk.

Background

This article explores nurses’ emotional well-being amidst the growing phenomenon that they are compelled to apply a multi-skills

approach in emotionally demanding work environments. Health services in South Africa present a challenging work environment for nurses.

These challenges include staff shortages, lack of training, overcrowded hospitals, insufficient health service management, lack of support

by supervisors, long work hours and task overload (Aucamp 2003:1,5; De Haan 2006:4; Hall 2004:30). Limited growth in the number of nurses

and the simultaneous increased number of patients due to high levels of poverty and the HIV and/or AIDS pandemic add to these challenges

and consequently put more demands on nurses (Mostert & Oosthuizen 2006:429; Subedar 2005:89).

One of the consequences of these challenges is that nurses working in health care services have to perform multi-skill tasks on a daily

basis (Triolo, Kazzaz & Wood 2005:45). In other words, they have to perform tasks for which they did not receive formal training and

which are outside their scope of practice (Adamovich et al. 1996:206). Although this approach is widely implemented, concerns exist

that its application is motivated by economical considerations rather than patient care, which could lead to lower quality care (Canadian

Association of Social Workers 1998). These factors may not only introduce medico-legal risks (Pera & Van Tonder 2004:172; Searle 2007:111;

Verschoor et al. 1996:53), but also lead to nurses experiencing stress and burnout. This, in turn, can have a negative impact on their

emotional well-being (Aucamp 2003:3; Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi 2006:96; Kozier et al. 2000:167; Smeltzer & Bare

2004:101; Van Vuren 2006:127).

Research in this area seems to focus on nurses’ well-being and satisfaction with their work environment (BÈgat, Ellefsen &

Severinsson 2005:221; BÈgat & Severinsson 2006:610). Boswell (2004:57) also focused on nurses’ well-being, concluding that

one of the most important considerations for nurses to leave the profession is difficult work circumstances, coupled with a feeling of

worthlessness resulting from a lack of support by management. Another example of research in this area is a study conducted by Ablett and

Jones (2007) on the resilience and well-being of hospice nurses rendering palliative care. In the South African context, Jooste (2003),

for example, explored nursing staff’s lack of involvement in and motivation for the delivery of quality health care, as well as the

role of nurse managers in addressing nurses’ motivational needs in the work situation.

Yet very limited evidence exist regarding the emotional well-being of the nurse in the multi-skill setting. The researcher’s own

experience as a professional nurse working in a multi-skill setting confirmed the emotionally demanding nature of this work environment.

Owing to a high workload and shortage of medical and nursing staff, nurses at this specific setting are expected to attend simultaneously

to trauma patients, patients in labour and pre-operative and post-operative medical patients, and to implement skills that are not necessarily

within their scope of practice.

Problem statement

In view of the aforementioned discussion and the researcher’s experience, the study sought to investigate (1) what the

nurse’s experience of working in a multi-skill setting is, (2) what the perception about coping mechanisms within a multi-skill

setting is, and (3) what can be done to promote the emotional well-being of nurses working in a multi-skill setting.

Objectives

The study thus aimed to (1) explore and describe the experience of the nurse working in a multi-skill setting, (2) explore and describe

the nurse’s perception about coping mechanisms within a multi-skill setting, and (3) formulate recommendations to promote the

emotional well-being of the nurse working in a multi-skill setting.

Definitions of key concepts

Level-2 hospital

The facility is defined as a district or regional hospital with maternity and specialist services (De Kock & Van der Walt 2004:2;

Uys & Middleton 2004:63). The Level-2 hospital where this research took place consists of a trauma unit, a theatre for uncomplicated

surgical procedures, a maternity section, and a 40-bed unit for patients in need of medical as well as pre-operative and post-operative

care. The hospital is served by visiting medical specialists and a psychologist, mostly on an outpatient basis and catering for private

patients (patients with a medical aid). Doctors visit the hospital only for rounds and are available afterwards only via a callout system.

Nurses, including professional and enrolled nurses and nurse assistants, are available 24 hours a day and are responsible for the care of

private and public health care patients in all the mentioned sections. Only two professional nurses are allocated per shift and are responsible

for taking the lead in patient care. Together with a small team of enrolled nurses and nurse assistants, they are responsible for the nursing

care in the trauma unit and maternity ward, as well as for the routine care of the medical and pre-operative and post-operative patients.

These nurses are consequently compelled to apply multiple skills in emergency situations, for example intubating patients and attending to

widely varying and complex health needs of patients.

Professional nurse

A person who is trained, competent and accountable for practicing nursing in an independent and comprehensive manner (South Africa 2005).

In this study, such professional nurses implemented multitasking in a Level-2 hospital where both private and public health services are rendered.

Enrolled nurse

A person who is trained, competent and accountable for rendering basic nursing care (South Africa 2005). In this study, such nurses were

defined as enrolled nurses who implemented multitasking in a Level-2 hospital where both private and public health services are rendered.

Nurse assistant

A person who is trained, competent and accountable for rendering elementary nursing care (South Africa 2005). In this study, nurse

assistants implemented multitasking in a Level-2 hospital where both private and public health services are rendered.

Multi-skill

An approach to care according to which nurses are expected to perform tasks outside of their scope of practice and for which they were

not originally trained (Adamovich et al. 1996:206). This concept also refers to the combination of two or more roles or skills

within a multi-skill role (Cameron 1997:1). In this study, multiple skills were expected from nurses in a Level-2 hospital where both

private and public health services are rendered.

Emotional well-being

The ability to acknowledge, accept and express one’s own emotions appropriately and accept personal limitations (Kozier et al.

2000:167), coupled with the ability to function comfortably and productively (Smeltzer & Bare 2004:101). This study focused on the emotional

well-being of the nurse working in a multi-skill setting.

|

Research method and design

|

|

Research approach

This study was performed according to an explorative, descriptive and contextual design with a qualitative approach. This

design was deemed appropriate, as it is applied when exploring and describing qualitative, subjective material in an attempt

to understand human experiences (Burns & Grove 2005:27; Polit & Beck 2006:16), in this case those of nurses working in

a multi-skill setting and their perceptions of coping mechanisms within this setting. This information was used to formulate

recommendations to promote the emotional well-being of these nurses.

Research method

Population

The population consisted of all the nurses (professional nurses, enrolled nurses and nurse assistants) working in a multi-skill

setting at a specific Level-2 hospital.

Sample

Because the entire study population worked in a multi-skill setting, the sample was all inclusive.

Data collection

Individual semi-structured interviews, as discussed by Brink, Van der Walt and Van Rensburg (2006:52), were used to collect data.

This data collection method allows the researcher to explore the experiences and perceptions of participants by asking questions

relating to the research problem and objectives, whilst being allowed to ask prompting and follow-up questions. Based on the research

objectives, the following interview questions were used:

• What is your experience of the multi-skill setting?

• What is your opinion on effective coping mechanisms within a multi-skill setting?

• In your opinion, what can be done to enhance the emotional well-being of the nurse within a multi-skill setting?

The researcher approached potential participants personally to explain the purpose of the research and expectations regarding participation.

This explanation was also provided in writing and adequate time was allowed for answering the potential participants’ questions about

the research. After informed consent was obtained, interviews were scheduled for a convenient time and place for each participant. Some

interviews were conducted in an office at the hospital, whilst others took place at the participants’ homes.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Field notes were compiled after each interview. A rich set of saturated data was

obtained during interviews with:

• three professional nurses

• six enrolled nurses

• one nurse assistant.

All participants were female and the sample included Black and White participants. The participants are collectively referred to as

‘nurses’ in the discussion of the results.

Data analysis

Results, in the form of transcribed interviews, were analysed using the method described by Creswell (2003:192). All the transcribed

interviews were reviewed to form a general impression of the responses. Themes were identified according to the research objectives

and grouped into columns. During a subsequent round of revision, notes were made pertaining to the identified themes. Each theme was

given a descriptive heading and divided into categories, with similar categories being grouped together. An independent co-coder was

appointed to co-analyse the data. After discussion with the co-coder the results were divided into appropriate main and subcategories.

Literature control

A literature control was conducted after data analysis, with the aim of confirming the results, pointing out unique results and reflecting

current knowledge about the research topic (Burns & Grove 2005:95). Databases used to search for relevant literature included Nexus

(National Research Foundation), SAePublications, ScienceDirect and EBSCOhost (Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, PsychInfo).

Ethical permission for the research was obtained from the Ethics committee of the North-West University (reference number 07K08).

Permission to conduct the research at the identified Level-2 hospital was subsequently obtained from the hospital manager. The

potential participants were then approached and the purpose and nature of the research, and potential benefits and risks (e.g.

the potential for emotional upset) were explained to them.

Ethical principles as discussed by Brink et al. (2006:31–34) were implemented. The principle of respect for participants

was implemented by obtaining informed consent, providing information on the study and offering participants the choice to withdraw.

The principle of beneficence was upheld by explaining the risk–benefit ratio to the participants, namely that they may not

experience immediate benefits from participating and that a counsellor would be available after the interview for the purpose of debriefing,

if needed. The principle of justice was adhered to through ensuring fair selection and treatment and the right to privacy, anonymity and

confidentiality.

The framework for trustworthiness as described by Babbie and Mouton (2004:276) and also Hek and Moule (2006:78) was applied in this research.

The framework entails four main criteria for trustworthiness, namely truthfulness, applicability, consistency and neutrality.

Truthfulness was ensured through:

• the researcher’s experience of working in a Level-2 hospital

• audio-recording interviews to ensure that the researcher did not forget or misinterpret the participants’ words

• writing field notes directly after each interview to ensure that no significant observations would be forgotten

• reporting the participants’ own words to indicate the range and variety of responses representing each topic

• continuing with data collection until data saturation was obtained

• analysing and discussing responses with a co-coder to ensure that the participants’ true opinions were identified (triangulation)

• consulting the two study supervisors to review the process and the findings

• comparing the findings with published studies and other literature (triangulation).

Applicability was achieved through rich description, whereby the research process, the characteristics of the participants and the context

are supplied to allow readers to determine to which extent the circumstances are similar to their own context.

Consistency was ensured by initial independent analysis by the researcher and co-coder, after which findings were compared during a consensus

meeting.

Neutrality was ensured by the researcher’s keeping the original interview schedule and the audio recordings, the transcripts, notes and

memos to provide an audit trail.

Four main response categories emerged, which were subsequently divided into subcategories. Participants’ experiences

were similar, irrespective of their position (professional nurse, enrolled nurse or nurse assistant) and are therefore presented

as a whole. As shown in Table 1, the following main categories were identified:

• positive experience of the multi-skill setting

• negative experience of the multi-skill setting

• personal coping mechanisms within the multi-skill setting

• promotion of emotional well-being within the multi-skill setting.

In the subsequent discussion of these response categories, statements by the participants are included in support of the results and

findings are discussed in relation to existing literature to facilitate critical reflection.

Positive experience of the multi-skill setting

Several reasons emerged for nurses’ positive experience of the multi-skill setting.

An opportunity to gain experience

Nurses experience the multi-skill setting as a learning environment as they work in different units and new patients are attended to in the

trauma unit daily. Nurses learn to function independently and to rely on their own decision-making skills. A participant stated: ’

With different people and different patients … from casualty and the whole ward, you learn a lot.’

The finding is in line with that of Adamovich et al. (1996:206), who state that the multi-skill setting provides an opportunity

for learning additional clinical skills, professional development, broadening one’s scope of practice and improving efficiency

through coordinating clinical services.

An opportunity to prepare for possible further studies

Nurses find opportunities to sharpen clinical skills in the multi-skill setting, which can be helpful when doing a bridging course to

improve their position. Participants stated:

’Even if I can go to be a staff nurse, I won’t have a problem. I don’t think I will struggle … it’s nice

for me to learn rather just to do the vital observations.’

’Normally they teach us, they say that we must know. I think also maybe if you want to study further, like if you want to be a

staff nurse or maybe [a] sister …’

This result appears to be specific to this study, as the researcher could not find any related existing literature confirming or contrasting

the finding.

An opportunity for task sharing

The multi-skill setting creates the opportunity for nurses to learn skills and gain confidence when assisting senior nursing staff to share

the workload, when required. A participant stated: ‘And, sometimes, if it’s very busy you can help the sister; you can put

up the new admission’s drip or maybe put up the catheter …’

Although Mathijs (2008:35) confirms that this phenomenon, known as task shifting, is widely practiced and respondents in this study

experienced it as a positive aspect of working in a multi-skill setting, they also shared that such situations are a source of stress

(see Table 1).

|

TABLE 1: Experiences, coping mechanisms and strategies to promote well-being of nurses working in the multi-skill setting.

|

Negative experience of the multi-skill setting

In spite of the positive experience, nurses also experience the multi-skill setting as stressful. The high workload, high level

of responsibility and staff shortages lead to the experience of the multi-skill setting as unpleasant and, sometimes, even intolerable.

Misrepresentation of the term ‘multi-skills setting’

Nurses were of the opinion that the term ‘multi-skill setting’ is justified in its use only when all the nurses working in

this setting possess the necessary clinical skills, as reflected by the following statements:

‘You can’t place someone who is supposed to work in casualty if you do not have the skills to work there. Most of the

time you do not have an idea of what is going on. So, it does not help that you have people who are so-called “multi-

skilled”.’

’They say it’s a multi-skill hospital; it is because we are working everywhere … Casualty, ward, everywhere we work.

Theatre, even though we are not supposed to work there, we must work in theatre as well.’

Literature supports the notion that ‘multi-skill’ and ‘multi-skilling’ are ambiguous terms, which are applied

and interpreted in various ways (Adamovich et al. 1996:206; Cameron 1997:1). There is little consensus about the responsibilities

of multi-skill staff, the skills and competencies that these staff should have or how to apply a multi-skills approach appropriately.

This is also true in the South African context, which confirms the need for research such as this study.

Stress brought on by staff shortages

Nurses experience staff shortages as stressful. It appears that the imbalanced representation of the different categories of nurses,

namely the shortage of professional nurses relative to the number of enrolled and assistant nurses, is a very specific area of concern,

as evident from the following statements:

‘[There is] a shortage of staff.’

’There’s a shortage of sisters.’

‘I think there is a shortage of staff and not everyone has the same skills.’

BÈgat et al. (2005:222) confirm that the nursing staff shortage impedes the nurse’s ability to render quality patient care,

which Aucamp (2003:20) confirms is perceived as a source of stress. Richards (2003:1) also mentions that the nature of work circumstances

is one of the main causes of work dissatisfaction amongst nurses.

Subjective consequences of task overload

Nurses experience several subjective consequences of task overload, namely increased levels of stress, physical and emotional exhaustion,

loss of concentration, work dissatisfaction and interpersonal conflict, all of which may have a negative influence on emotional well-being.

The following statements support this finding:

‘It’s strenuous and difficult.’

’You become tired; sometimes you get overloaded …’

‘You loose concentration [in] your work.’

’Sometimes you forget what you were doing.’

‘Sometimes you don’t finish your work.’

‘You feel stressed and you feel guilty.’

’It’s difficult, because you are one nurse and there are many things to do at one time.’

’You feel stressed and tired and sometimes you get confused.’

Aucamp (2003:21) confirms that workload is a determining factor in emotional exhaustion. BÈgat et al. (2005:228) further mention

that the less time a nurse has to complete tasks, the more physical symptoms of stress are evident or experienced. Demir, Ulusoy and

Ulusoy (2003:823) also found that work overload leads to burnout and work dissatisfaction.

Unreasonable staff allocation

Nurses find the allocation of staff in the multi-skill setting as unreasonable and confusing. They are rotated between wards in an unorganised manner and have to be prepared to work in different specialties owing to the unpredictable nature of patient presentation at a hospital. Participants shared the following:

’We are working stressfully … [in] the wards and casualty at the same time.’

‘I know they say this is a multi-skill hospital. Actually, I think it’s because you work all over, casualty and the ward.

And we have to work in [the] children’s ward. We have a paediatrics ward as well. I just see everything

[as] disorganised here.’

‘Maybe the ward is full and we are maybe three assistant nurses. We have to go up and down: casualty, private ward, children’s

ward.’

This seems to be a unique finding of this research.

Duties beyond scope of practice

Nurses experience stress and fear when they are forced to practice outside their scope of practice. Sustained exposure to this stressful

situation leads to burnout with a consequent negative effect on emotional well-being. Participants made the following statements:

’We don’t have enough staff and some of the things we [just] cannot do. Our scope doesn’t allow us

to do that.’

’We always work outside of our scopes, every day.’

’I’m not even trained to do the SSD [central sterilisation department], but I’m doing those things.’

’It seems as if it’s not my scope of practice, it makes me stressed … because I’m putting myself in danger.

What if they [the Nursing Council] find me doing those things and I’m not supposed to do those things?’

Stewart and Arklie (1994:183) also found that nurses whose roles are not clearly defined and who perform tasks beyond their scope

experience increased levels of burnout.

Insufficient resting time

Some nurses were of the opinion that there are not enough opportunities to rest during the work day, as reflected by the following statements:

’You have to go on tea. Sometimes, because there’s a shortage [of staff], you can’t even go on tea.’

’You can’t even go to lunch sometimes. You [have] not [gone] since the morning.’

This seems to be a unique finding of this research.

Negative perception towards management

Nurses indicated a negative perception towards the mangement of the hospital owing to management not attending to the nurses’

emotional needs. The following statements illustrate this finding:

’… but the management is not right … they don’t care about the employee’s feelings.’

’They don’t care about our opinions.’

’It breaks your self-esteem … you don’t feel motivated.’

’You satisfy their needs. They don’t care.’

Boswell (2004:56) and Mynhardt (2006:547) both found that health care workers’ perception about management has an important effect

on their level of motivation in the workplace. The more nurses perceive that they are being treated fairly, the more they are engaged

with their work and motivated to perform additional tasks.

Personal coping mechanisms within the multi-skill setting

Task prioritisation

Nurses were of the opinion that prioritising is an important coping mechanism in the multi-skill setting. Nurses felt in control when they

could complete more important tasks before performing less important ones. This decreases stress and creates an effective work environment.

It also contributes to work satisfaction and emotional well-being. The following statements support this finding:

’I try to divide my time …’

’I prioritise.’

’I complete one task at a time, and you do what you can. I finish the most important things first and then I can start with the

next thing. You then feel in control of things.’

Literature confirms that the degree to which nurses have time to plan ahead has a definite influence on their general well-being

(BÈgat et al. 2005:227).

Faith

Nurses rely on their faith in God as a coping mechanism in the multi-skill setting. The following statements support this finding:

’ I just pray: “God, help me”.’

’Just maybe, that you can pray and just believe every day. Because if you trust God, He will help you to cope.’

This seems to be a unique finding of this research, as literature to support this finding could not be found.

Self-motivation

Nurses often use self-motivation as a coping mechanism in a multi-skill setting, as illustrated by the following statements:

’I tell myself that the work must be done, I have to keep going.’

’I just tell myself that this thing doesn’t have to bother me. And I don’t get stressed. It doesn’t help

to become stressed. It only makes things worse.’

Coon (1998:407) describes self-motivation as continued positive thinking and behaviour and the ability to persevere in spite of negative

circumstances. BÈgat et al. (2005:227) confirm that nurses use self-motivation to cope with difficult work circumstances.

Mutual support amongst colleagues

Nurses experience mutual support amongst colleagues as very important within the multi-skill setting. It serves as a coping mechanism and

is a motivational factor in this stressful work environment. The following statements support this finding:

’Sometimes we help each other.’

‘You learn how to co-operate with people. Colleagues … are not [all] the same.’

’You help each other.’

’You know what? Actually, we are working as a team, but sometimes it’s difficult to work with some other people because

… instead of working like maybe I want [to work] – we have to work together – they just remain behind

and then they push you to do the things [to complete the tasks].’

Trust and mutual support amongst colleagues are described by both Boswell (2004:57) and Van Rhyn and Gontsana (2004:26) as important

contributory factors to work satisfaction. Aucamp (2003:4) also states that nursing colleagues can be important resources amongst one

another to aid in the management of stress in the workplace. Similarly, Levert, Lucas and Ortlepp (2000:37) report that limited support

amongst colleagues is an integral cause of burnout.

The promotion of the emotional well-being of nurses within the multi-skill setting

The promotion of emotional well-being on a personal level, as well as at management level emerged from the research.

Personal promotion of emotional well-being

Nurses mentioned several strategies that can be applied at a personal level to promote emotional well-being. These further categories include

the following:

In-service training: Nurses suggested in-service training as a strategy for the promotion of emotional well-being. The following

statements illustrate this finding:

’Maybe training … can also help.’

’I think if maybe you gain more knowledge. [Through] training people gain more knowledge and it will help them in a

ward maybe to do their work properly. And quality work … You can improve them – and then they will also feel more

self-confident in their work.’

’It will decrease stress.’

Muller (2005:141) confirms that nurses should receive the necessary training to ensure competent performance.

Support system: A support system, in the form of training about topics related to emotional well-being, was suggested. This

could provide nurses with practical advice to cope with stress. Participants also suggested that establishing a ‘haven’

could be valuable in the promotion of their emotional well-being. They explained this ‘haven’ as a place where nurses can

go to talk about stressful experiences and obtain perspective in order to once again function effectively in the workplace. The

following statements reflect their views:

’… might sometimes need counselling as others, other things in hospitals are [traumatic].’

’Maybe even to give nurses education on mood swings. Sometimes, others … can be rude if they like …’

’Sometimes when you feel, when you feel that work is too much, [that] there’s too much work and you get too busy,

then you become frustrated and you become rude.’

Hall (2004:34) also suggests that employers should support employees by presenting programmes on the management of stress, as well as

creating opportunities for counselling. These services should be avaialable free of charge for nurses of all categories (Hall 2004:34).

In addition, the former Minister of Health, Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, promoted the notion of ‘wellness centres’ for

health care workers to promote their well-being (Khumalo 2008:9)

Managerial involvement to promote emotional well-being

Nurses suggested several practical strategies whereby management can improve the work environment, consequently contributing to the

emotional well-being of nurses.

Appointment of additional staff: Nurses felt that the appointment of additional permanent staff is essential to ensure that there

are enough human resources available on a daily basis, as reflected by these statements:

‘Firstly, they can try to have more staff.’

’I think they can employ more nurses.’

’First thing they [the management] must do [is to] employ people and stop using agencies.’

’They should at least appoint people permanently.’

’Sometimes there are too few staff …’

’There’s a lot of people on the roster but they don’t want to call people to come on duty. And they don’t want

to give people employment … they only use agencies.’

Literature confirms that inadequate staff numbers not only hold risks for patient safety, but can also have a negative impact on the well-being

of the nurse (American Nurses Association 2007).

Appropriate staff allocation: Nurses explained that they found it stressful to have to work in various wards or sections and then be

held accountable for the care of all the patients. Statements to support these views are as follows:

’I think there should be specific people that are always there for casualties … and a doctor also in casualties. I think

there should be a permanent [attending] doctor for casualties …’

’… maybe [if] there are nurses for theatre, nurses for casualties and nurses for the ward.’

This seems to be a finding specific to this study.

Managerial involvement: Nurses perceived management not to be adequately involved with staff on a personal level, as illustrated

by the following statements:

’Maybe from the hospital management, if they can maybe try to understand the staff …’

’When they voice [complaints], they must help them. Not to just leave them like that …’

’We need support from our hospital manager, the matron, the ward manager, unit manager. I think if they can [set up]

meetings with nurses and … communicate with the nurses more, it can be better.’

’They just sit in their office and they wait for people to come and say who did what.’

’They must treat nurses equally.’

’… they must ask for opinions from nurses.’

Boswell (2004:59) confirms that, in general, there is a lack of trust between nurses and management, because of nurses’ perception

that their well-being does not receive enough attention.

The sample consisted only of female nurses, whilst the opinion of male nurses may have contributed to the results of the study.

In addition, some nurses were reluctant to participate in interviews after work hours, leading to fewer participants being available.

Recommendations for further research, nursing education and nursing practice were formulated. Recommendations for nursing practice

focus on the promotion of the emotional well-being of the nurse within a multi-skills setting.

Recommendations for further research

Further research on the following research topics related to the emotional well-being of the nurse in the multi-skill setting is recommended:

• specialised training

• management style

• support networks

• task allocation and productivity

• patient experience of the quality of health care in the multi-skill setting

• scope of practice

• economic implications of the multi-skill setting

• personal circumstances of nurses working in a multi-skill setting

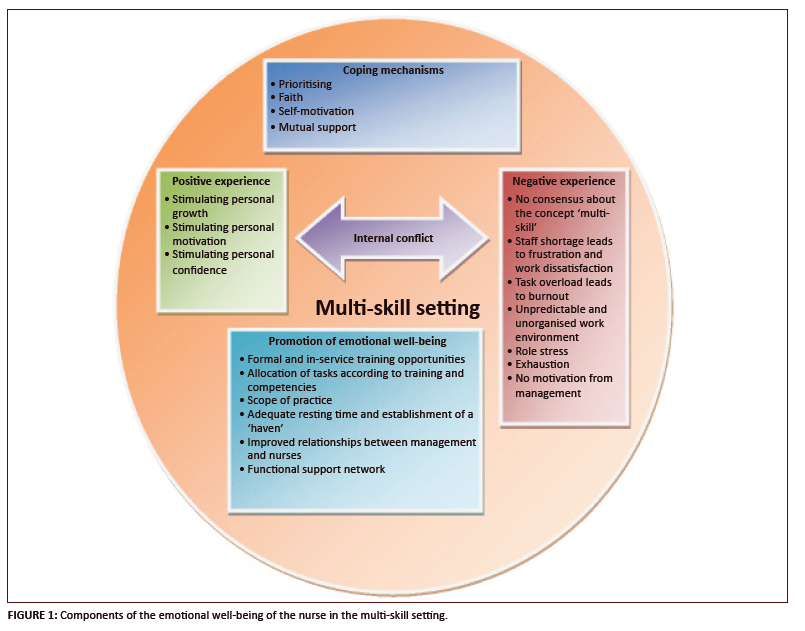

• relationships between concepts portrayed in Figure 1 (also see later for a discussion).

Recommendations for nurse education

Participants suggested in-service training on specific topics as a strategy to promote their emotional well-being. In addition, it may be

valuable to include the recommendations for promoting the emotional well-being of nurses in formal as well as informal training (see ’

Recommendations for nursing practice’).

Recommendations for nursing practice

These recommendations describe how emotional well-being of nurses working in the multi-skill setting can be promoted. Firstly, adequate

in-service and formal training opportunities should be provided. This should include appointment of training staff, encouragement of

‘on-the-spot’ training and provision of financial support for further training. Furthermore, tasks should be allocated according

to nurses’ individual training and capabilities. The scope of practice of each nursing category should be available in writing and

should be monitored. Nurses should be allowed time to rest during shifts and a suitable area for debriefing should be available. Improvement

of relationships between management and nurses should be a priority. Also, the strengths nurses display, for example their coping mechanisms

as emerged from this research, should be acknowledged and promoted. Lastly, a functional support system for nurses should be established.

Application of these recommendations may contribute to creating a positive work environment that is less stressful and more conducive to

promoting the emotional well-being of the nurse. This, is turn, may lead to nursing staff being more motivated towards and engaged in their

work and so contribute to quality nursing care.

The purpose of this study was to explore and describe the experiences of nurses working in the multi-skill setting and their perception

about coping mechanisms within this setting. Findings provided insight into the unique experiences and perceptions of these nurses, which

allowed recommendations for promoting their emotional well-being to be formulated.

The results showed that nurses have contrasting experiences of the multi-skill setting and conclusions from the study are presented

schematically in Figure 1.

|

FIGURE 1: Components of the emotional well-being of the nurse in the multi-skill setting.

|

|

On the one hand they experience it as a stimulating setting that offers learning opportunities, but, on the other hand, they also experience

it as an unorganised setting associated with high demands such as responsibility for all wards in the hospital in a high-paced environment,

where they are compelled to perform tasks beyond their formal capabilities. This leads to fear and internal conflict, which have a negative

influence on nurses’ emotional well-being. Nurses furthermore experience a lack of support and engagement from management, leading to

demotivation. Nurses use personal coping mechanisms such as task prioritisation, faith, colleague support and self-motivation to cope in the

multi-skill setting.

Ablett, J.R. & Jones, R.S.P., 2007, ‘Resilience and well-being in palliative care staff: A qualitative study of hospice nurses’

experience of work’, Psycho-Oncology 16, 733−740.

Adamovich, B., Davis-McFarland, E., Green, W.W. & Pietranton, A.A., 1996, ‘Multiskilled personnel’, Audiology and

Speech-Language Pathology 4, 205−213.

American Nurses Association, 2007, Staff nurses, viewed 22 December 2007, from

http://nursingworld.org/EspeciallyForYou/stafftesting.aspx

Aucamp, J.M., 2003, ‘Occupational stress of professional and enrolled nurses in South Africa’, MA mini-dissertation,

Department of Nursing, Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education.

Babbie, E. & Mouton, J., 2004, The practice of social research, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, Cape Town.

BÈgat, I., Ellefsen, B. & Severinsson, 2005, ‘Nurses’ satisfaction with their work environment and the outcomes of clinical

nursing supervision on nurses’ experiences of well-being – A Norwegian study’, Journal of Nursing Management

13, 221−230.

BÈgat, I. & Severinsson, E., 2006, ‘Reflection on how clinical nursing supervision enhances nurses’ experiences of well-being

related to their psychosocial work environment’, Journal of Nursing Management 14, 610−616.

Boswell, M., 2004, ‘The effect of closed versus more liberal visitation policies on work satisfaction, beliefs, and nurse retention’,

MSc thesis, Department of Nursing, East Tennessee State University.

Brink, H., Van der Walt, C. & Van Rensburg, G., 2006, Fundamentals of research methodology for health care professionals, 2nd edn.,

Juta, Cape Town.

Burns, N. & Grove, S.K., 2005, The practice of nursing research: conduct, critique, and utilization, 5th edn., Elsevier Saunders,

St. Louis.

Cameron, S., 1997, ‘Finding the perfect mix: Role-redesign initiatives’, in Ontarion Hospital Association, viewed 14 August 2007,from

http://www.oha.com/hospitalperspectives/findingtheperfectmix.htm

Canadian Association of Social Workers, 1998, CASW statement on multi-skilling, viewed 02 March 2008, from

http://www.casw-acts.ca/practice/recpubsart2.htm

Coon, D., 1998, Introduction to psychology, 8th edn., Brooks/Cole, Washington.

Creswell, J.W., 2003, Research design: qualitative and quantitative approaches, 2nd edn., Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Csikszentmihalyi, I.S. & Csikszentmihalyi, M., 2006, A life worth living: Contributions to positive psychology, Oxford University

Press, New York.

De Haan, M., 2006, The health of Southern Africa, 9th edn., Juta, Cape Town.

De Kock, J. & Van der Walt, C., 2004, Maternal and newborn care. A complete guide for midwives and other health professionals,

Juta, Pretoria.

Demir, A., Ulusoy, M. & Ulusoy, M.F., 2003, ‘Investigation of factors influencing burnout levels in the professional and private

lives of nurses’, International Journal of Nursing Studies 40(8), 807−827.

Hall, E.J., 2004, ‘Nursing attrition and the work environment in South African health facilities’, Curationis 27(4),

28−36.

Hek, G. & Moule, P., 2006, Making sense of research: an introduction for health and social care practitioners, 3rd edn.,

Sage, London.

Jooste, K., 2003, ‘Promoting a motivational workforce in nursing practice’, Health SA Gesondheid 8(1), 89−98.

Khumalo, G., 2008, ‘Wellness centres to help workers deal with stress’, HOSPERSA Today 14(2), 9.

Kozier, B., Erb, G., Berman, A.J. & Burke, K., 2000, Fundamentals of nursing: concepts, process, and practice, 6th edn., Prentice

Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J.

Levert, T., Lucas, M. & Ortlepp, K., 2000, ‘Burnout in psychiatric nurses: Contributions of the work environment and a sense of

coherence’, South African Journal of Psychology 30(2), 36−43.

Mathijs, F.F., 2008, ‘Task shifting: an old practice with a new name’, Nursing Update 32(1), 34–35.

Mostert, K. & Oosthuizen, B., 2006, ‘Job characteristics and coping strategies associated with negative and positive work-home

interference in a nursing environment’, South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 9(6), 429−443.

Muller, M., 2005, Nursing dynamics, 3rd edn., Heinemann, Sandown.

Mynhardt, J.C., 2006, South African supplement to social psychology, 2nd edn., Pearson, Cape Town.

Pera, S.A. & Van Tonder, S., 2004, Ethics in nursing practice, 4th edn., Juta, Cape Town.

Polit, D.F. & Beck, C.T., 2006, Essentials of nursing research: methods, appraisal, and utilization, 6th edn.,

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

Richards, R., 2003, ‘The health professional brain drain’, Education for Health 16(3), 262−264.

Searle, C., 2007, Professional practice: a South African nursing perspective, 4th edn., Heinemann, Sandton.

Smeltzer, S.C. & Bare, B.G., 2004, Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing, 10th edn., Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

South Africa, 2005, Nursing Act 33 of 2005, Government printer, Pretoria.

Stewart, M.J. & Arklie, M., 1994, ‘Work satisfaction, stressors and support experienced by community health nurses’,

Canadian Journal of Public Health 85(3), 180−184.

Subedar, H., 2005, The nursing profession: production of nurses and proposed scope of practice, South African Nursing Council, Pretoria.

Triolo, P.K., Kazzaz, Y. & Wood, G.L., 2005, ‘Developing clinical nurse leaders at the unit level’, Nurse Leader

3(2), 45−48.

Uys, L.R. & Middleton, L., 2004, Mental health nursing: a South African perspective, 4th edn., Juta, Cape Town.

Van Rhyn, W.J. & Gontsana, R., 2004, ‘Experiences by student nurses during clinical placement in psychiatric units in a

hospital’, Curationis 27(4), 18−27.

Van Vuren, A, 2006, Psychology for nurses, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Verschoor, T., Fick, G.H., Jansen, R. & Viljoen, D.J., 1996, Verpleegkunde en die reg, Juta, Kaapstad.

|

|